The United States has qualified for every World Cup since 1990. Only once in that span did the Americans need a result on the final day of qualifying. That came in 1989 when the U.S. traveled to Trinidad and Tobago needing nothing less than a win to procure a trip to the 1990 World Cup. The USMNT again travels to Trinidad and Tobago on Oct. 10 needing a result to extend its streak to eight straight World Cup appearances.

The team that qualified in 1989 looked nothing like today’s modern USMNT. Before the 1994 team hosted the World Cup in front of record crowds, before the run to the 2002 World Cup quarterfinals, before winning a World Cup group with England in 2010, there was the ragtag 1989 team of college players and struggling semi-pros. Before Eric Wynalda, before Landon Donovan, before Christian Pulisic, there was Paul Caligiuri.

The modern growth of soccer in the United States dates back to the trip the USMNT made to Trinidad and Tobago on Nov. 19, 1989, the final day of qualifying for the 1990 World Cup. One match set the U.S. on its path to becoming a regional soccer powerhouse. One match could have set the nation back decades. It was the soccer version of the shot heard ’round the world.

Unknown Hero

Paul Caligiuri was an unlikely hero for a country that didn’t know he existed. Heading into the 1990 World Cup, the U.S. hadn’t qualified for the world’s biggest event since 1950, but the USMNT was finally getting close. The explosion of popularity — and the eventual demise — of the NASL spoke to the promise of soccer in a country crazy about baseball, American football and basketball. The U.S. would host the World Cup in 1994, but there were rumors the country would lose the tournament if they couldn’t qualify for the 1990 edition. (Funny that doesn’t seem to be an issue for Qatar now.)

With Mexico banned from the 1990 World Cup for using an overage player in a youth tournament, this was the United States’ best chance to qualify in decades. Costa Rica was already in, but Trinidad and Tobago and the U.S. were fighting for the final berth. Tied with Trinidad and Tobago on nine points but trailing on goal differential with one match to play, the task at hand was simple: Win and you’re in. A draw or loss would send Trinidad to its first ever World Cup.

The team had few members playing legit professional soccer; none would ever be recognized on the streets in the U.S. Most were still in college or making a small amount of money from contracts with U.S. Soccer Federation. The Americans flew to the Caribbean nation on a plane named Destiny and destiny was there for the taking.

This, but with tens of thousands of screaming fans. Photo: @geoffwnjwilson | Twitter

The match was played in front of an overflowing crowd at Trinidad and Tobago’s National Stadium, a jubilant throng hopeful of becoming the smallest country to ever qualify for the planet’s biggest tournament. Thousands met the U.S. team at the airport and a party raged through the night before the match outside the team hotel in classic CONCACAF fashion. The country essentially declared the match day a national holiday in anticipation of victory at home, where they were undefeated in the qualifying round.

It Went Up, Then It Came Down

Caligiuri wasn’t yet a regular starter. He wasn’t even a central midfielder, more often deployed as a defender. But on Nov. 19, 1989, coach Bob Gansler placed Caligiuri in central midfield for the first and only time among his 110 national-team caps.

The Californian was given one job and one job alone: prevent playmaker Russell Latapy from feeding striker Dwight Yorke. While York wasn’t yet the star he would become — he scored 189 goals in England, including 65 for Manchester United — there was a clear need to prevent service to the most dangerous player on the pitch.

For most of the match, Caligiuri did his job well. Except for one moment when he defied his coach’s demands and went forward. In the 30th minute, Tab Ramos hit a bouncing ball to Caligiuri with defender Kerry Jamerson running out to meet him. Instead of playing a safe pass backward and returning to his defensive position, Caligiuri did the unimaginable.

First, the defensive-minded player used his stomach/groin to propel the ball not backward but forward. He took a slight pause, enough time for both him and Jamerson to ponder what would come next. Caligiuri, who up to that point looked to be going in slow motion, then flicked the ball with his right foot past Jamerson and warped past the defender. With the ball still bouncing on the less-than-stellar surface, Caligiuri cocked back his left leg and swung it at the ball for a powerful volley from 30 yards out.

The ball went up and up, well above the crossbar. Then, dramatically, it swooped down and down. Trinidad and Tobago goalkeeper Michael Maurice made a desperate lunge, but it was in vain. Caligiuri’s shot found the bottom right corner and the back of the net. The U.S. led 1-0. The stadium fell silent, outside of a handful of Americans who were probably related to the players. The World Cup was within reach.

Launch Pad

Of course, there were still 60 minutes of football to be played that day. Caligiuri returned to his defensive duties. Tony Meola, sporting a baseball cap in the second half to shield his eyes from the sun and our eyes from his mullet, made several sprawling saves to deny Yorke and the Trinidadians.

Announcer JP Dellacamera, who back then still called himself John Paul and whose voice was not yet one of the most recognizable in American soccer, called the match but few people in America watched on TV or even knew the game was taking place. His voice grew more and more frantic as the match went on and the U.S. inched closer to Italy.

Ultimately the United States held on to win 1-0. Caligiuri’s strike sent the U.S. to the World Cup for the first time in four decades. The team has qualified for every World Cup since, albeit as host in 1994. With seven straight World Cups, the U.S. has one of longest active streaks in the world, more than England, Mexico and the Netherlands. Major League Soccer debuted in 1996 and has steadily grown into one of the most successful leagues in the world. The U.S. has won six Gold Cups (only Mexico has more with seven).

All because of Caligiuri’s goal (and the performance of the rest of the team). As Sports Illustrated once put it: “His goal was nothing less than the launch pad for U.S. Soccer’s modern era, 25 years of growth that was hardly inevitable.”

SI ranked it the most significant goal in U.S. soccer history, ahead of Landon Donovan’s last-minute winner against Algeria in the 2010 World Cup and Joe Gaetjens’ winner in the 1950 World Cup to beat England — even ahead of Brandi Chastain’s 1999 penalty kick against China to win the World Cup.

Past To Present

The U.S. went on to lose all three matches in the 1990 World Cup in Italy. Caligiuri scored again (one of his five national-team goals) in a 5-1 loss to Czechoslovakia with Eric Wynalda being sent off before the Americans redeemed some respect with a 1-0 loss to Italy in Rome that they nearly equalized late. The tournament ended with a 2-1 defeat to Austria, the only two goals Austria scored in Italy.

Nonetheless, the Americans reached the World Cup, a huge learning point for a roster featuring a number of future stars of the game in the States, including Tony Meola, John Harkes, Tab Ramos, Marcelo Balboa and Kasey Keller. They played for teams like the Albany Capitals, San Francisco Bay Blackhawks, San Diego Sockers and UCLA Bruins back then, the best clubs available for the top American soccer players at the time.

Since then, Americans have played for some of the best clubs in the world, from Manchester United and AC Milan to Borussia Dortmund and Arsenal. The U.S. now expects to be at every World Cup and they don’t rely on a bunch of kids with little experience to qualify.

Only now, a bunch of seasoned professionals go into this weekend with their World Cup lives at their feet. No matter how the U.S. performs against Panama on Friday at home, the trip to Trinidad and Tobago will require a result for the Americans to book a trip to Russia. That trip may take a detour if the U.S. finishes fourth in the Hex and must play an intercontinental playoff against Syria or Australia.

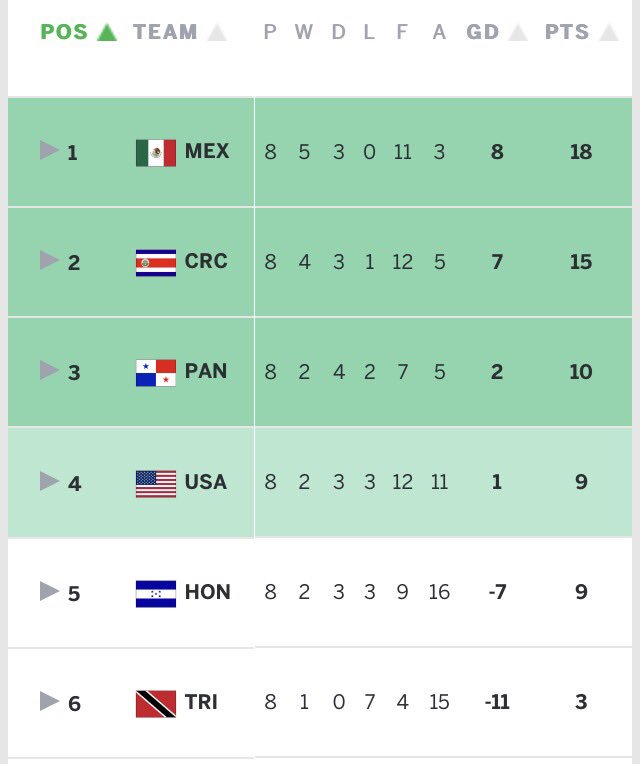

CONCACAF Hex standings with two matches to play. Photo: @AndrewDasNYT | Twitter

For their part, Trinidad and Tobago still has an outside shot of finishing fourth in qualifying, though the country must win its final two matches and hope for a lot of help.

But as the Americans travel to Couva to play in the 10,000-seat Ato Boldon Stadium on Oct. 10, they can look back to history and know they’ve qualified for the World Cup in Trinidad and Tobago once before.