By any measure, 2015-16 is shaping up to be the tightest, most intriguing Premier League season in decades. Yes, we’ve had close title races before, not least Man City winning the league on goal difference in the dying seconds of 2011-12. But the complexities and ebbs of the season to-date are unparalleled in recent years. Leicester City sit top of the table, Chelsea continue to languish towards the bottom, while newcomers Bournemouth defeat the reigning champions and England’s most successful team in successive weeks. This season’s champions will likely record the lowest points total seen in over 15 years – a clear sign not of dwindling quality, but of increased competition.

So who, or what, do we have to thank for this magnificent maelstrom? In a word: Greed.

Everything the Premier League does is designed to increase its revenue from television, with players, clubs and supporters a tertiary concern; the promotion of the “product” is paramount. Take, for example, the marginalisation of the traditional Saturday, 3pm kick-off so beloved of fans. Last weekend just four of the EPL’s 10 fixtures kicked off mid- Saturday afternoon, with the other games spread over the weekend for the benefit of global television audiences.

There are myriad other examples of the Premier League’s commercialization over the last decade, but Richard Scudamore’s “prostitution” of the English domestic game has undoubtedly been successful: the league’s TV packages have increased from $500 million per season for 2004-07 to $2.5 billion per season for 2016-19.

And the fundamental importance of this greed, and all the money that’s sloshing around as a consequence, is this: it’s greatly reduced the in-built advantage once enjoyed by England’s “Top Four” clubs.

The Premier League's Chief Executive, Richard Scudamore, has transformed his product into a cash cow. (@Irapisurn | Twitter)

Greed has had a three-fold impact on competition within the Premier League. Firstly, it’s dulled the relative financial importance of Champions League participation. Ever since UEFA’s foremost club competition expanded to include multiple teams from a single league (making a mockery of its moniker in the process), a cabal of three-to-four clubs have utterly dominated the EPL. Super-charged by the additional revenue they garnered from consistent appearances in the UCL, the likes of Manchester United, Arsenal and Chelsea stretched away from the EPL’s lower echelons to create a truly two-tier competition, in which the same four clubs nearly always finished inside the top four, thus qualifying again for another Champions League cash injection.

But the money on offer from the Champions League no longer provides such a sizeable boost to those who compete in it. Television revenue for the Premier League is increasingly vast, and because it’s shared relatively equally among all 20 teams in the competition, the importance of the additional money that comes from the Champions League is diminished.

In 2009/10, the average additional revenue enjoyed by the four Premier League teams competing in the UCL equated to 71% of the average TV / prize money shared out across all 20 EPL teams; in 2014/15 that percentage plummeted to just 34%, despite Champions League revenue actually increasing in Euro terms. It’s a percentage that is going to shrink even further when the new, improved EPL television deal kicks in next year, against which many teams are already spending.

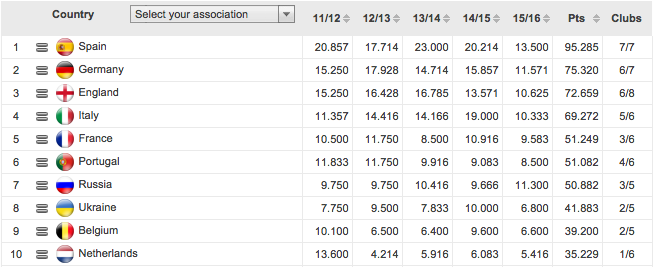

The second knock-on effect from the Premier League’s promotion of itself above all else is that those clubs who do qualify for the Champions League don’t enjoy the support of their domestic league. Take the fixture list as just one of many examples: nearly every European league except the EPL seeks to accommodate their UCL representatives by arranging Friday fixtures or home ties preceding mid-week European action. But that sort of flexibility doesn’t sit with the Premier League’s TV-driven revenue model, and the upshot is that teams competing in the Champions League are less rested and therefore less likely to progress deep into the competition. Again, look at the table below, which shows the EPL’s dwindling UEFA coefficient.

Photo: UEFA

Finally, the vast wealth that’s now available to every Premier League team means even smaller outfits can compete for top-tier talent worldwide. While a Manchester United will always have more cachet and commercial pull than a West Brom, the gulf between the revenue flowing into England and the rest of the world is so great that many players will choose middling EPL teams over more storied continental clubs. Dimitri Payet’s move from Marseille to West Ham, or Xherdan Shakiri’s move from Inter to Stoke, are just two of many examples that played out this summer. Every club can only keep so many players happy, and while a Zlatan Ibrahimovic will always choose the Stade de France over Selhurst Park, a Yohan Cabaye will happily swap big money at PSG for big money and playing time at Crystal Palace.

All of which has helped to close the gap between the Premier League’s biggest clubs and the rest, bringing greater competition and unpredictability back to England’s top-flight. The EPL’s relentless pursuit of readies has dented the relative and actual additional income that comes with competing in the Champions League, while making nearly every club in the EPL a more attractive proposition than 99% of the world’s other professional clubs. While you still can’t say that all 20 teams are capable of winning the title, even relegation favorites can be counted on to beat teams challenging for the top spot.

There are, of course, downsides to this influx of money, not least in how we, the supporters, access the Premier League’s 380 games a season: ticket prices are astronomically high, while subscription fees for TV packages showing the EPL are increasingly prohibitive. But when it comes to the narrow confines of the Premier League as a competitive spectacle, greed, for want of a better word, is good.