Men's college soccer in the United States is an anomaly. No other country sends potential professional athletes to academic universities instead of athletic academies like the U.S. While this is the accepted norm in football and basketball, the two most popular sports in the country, soccer operates differently throughout the world.

NCAA soccer is an interesting beast. On one hand, it’s an existing structure capable of providing additional training to thousands of soccer players that otherwise might not get the chance to play after graduating high school. On the other hand, due to strict restrictions on practice times, short seasons and an uneven playing field, men's college soccer is not an ideal institution for producing professional soccer players on the global level.

There are a lot of issues with men's college soccer (and soccer in general) in America but one particularly beguiling aspect of it is the inequity in the schools that win the most national championships and where the country’s best players come from. The areas producing the best soccer players have little to no correlation to the universities that have the most success at the NCAA level. This is one of the major problems with soccer in America.

Site of the 2017 Men's college soccer championships. Photo: @EC_MensSoccer | Twitter

Stanford won its third straight Men’s College Cup championship on Sunday and while California is a hotbed of soccer talent, it’s typically Southern California (San Diego, L.A.) producing players like Landon Donovan. For the most part, universities with the most success in men's college soccer are not located in areas where most USMNT players have come from in the last 20 years.

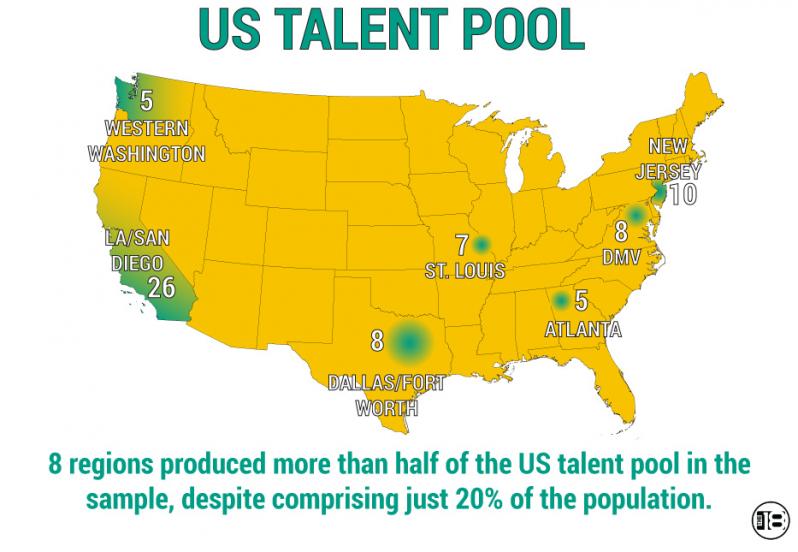

Over the last two decades, looking the 127 USMNT players who grew up in the U.S., more than half of those players came from eight regions in which a mere 20 percent of the U.S. population lives. And yet, only a small portion of schools has won NCAA titles from those eight regions in the last 20 years, and none from the southern parts of the country.

The San Diego/Los Angeles region produced more USMNT players than any other region, so you’d expect schools in Southern California to dominate the soccer landscape. While UCLA has won four national titles, only two have come in the last 20 years and none since 2002.

The D.C.-Virginia-Maryland area has produced plenty of talent over the years and is the one region that appears to be succeeding at the college level and in producing USMNT players. With Virginia and Maryland both having won a pair of national titles this millennium, the region is the exception. You can thank Bruce Arena’s influence for Virginia’s success, having led the Cavaliers to four straight titles in the early ’90s.

The other hotspots, however, have little to no success at the NCAA level, particularly in recent decades. New Jersey, Dallas-Fort Worth, St. Louis, Atlanta and Western Washington are some of the top producers of talent but none of those regions have any history of success winning national championships with the exception of St. Louis, which hasn’t won a national title since 1973. (Saint Louis University leads all schools with 10 national titles but all came more than four decades ago, when the landscape of U.S. soccer was completely different.)

There are many reasons for this but one major culprit is American football. Texas and Georgia (and Missouri, to an extent) are firmly entrenched in football country and most major universities in the Southeast choose to focus on the football played with one’s hands instead of the football played with one’s feet.

Texas, despite being one of the most populous, wealthy states in the union and a major producer of soccer talent from the DFW Metroplex, Houston and San Antonio, has exactly one major NCAA Division I university that competes in men’s soccer. For Texans who want to play Division I college soccer in state they have but one choice: Southern Methodist University. (Smaller schools Houston Baptist, Incarnate Word and UT Rio Grande Valley have also recently added D-I programs.)

That’s why players like Richardson’s Jeff Agoos (Virginia), Nacogdoches’ Clint Dempsey (Furman), Houston’s Stuart Holden (Clemson) and Dallas’ Omar Gonzalez (Maryland) went out of state for college. It’s why going abroad at an early age was such an easy choice for young Texans McKinze Gaines, Emerson Hyndman, Weston McKennie and Keaton Parks.

Rural Texas native Clint Dempsey had to go to Furman in South Carolina to play men's college soccer. Photo: @FurmanPaladins | Twitter

The reason for this is simple: Colleges are restricted by Title IX regulations to provide equal opportunities for men and women. For every athletic scholarship given to a man, one must be given to a woman. There’s nothing wrong with that regulation, but it creates an environment where schools across the country (especially the South) choose to focus on football at the expense of other men’s sports, notably soccer. Thus, players from these areas forgo the college route, end up at out-of-state schools or just give up on soccer.

In the Pacific Northwest, which has some of the best soccer fans in the country, the story is similar to the South. Only Washington and Oregon State compete in the Pac-12, with Washington State and Oregon both choosing not to field teams. But at least they have a couple schools competing whereas the SEC and Big 12 conferences don’t support any men’s college teams.

New Jersey is a bit different. Although the largest state college, Rutgers, has men’s soccer, the Scarlet Knights don’t have much of a history of success, reaching the final four three times between 1989 and 1994. Perhaps its biggest contribution to soccer (or worst, depending on your outlook) is its most famous football alumni: Alexi Lalas.

Princeton has won seven national championships in soccer (all before 1958) and was where Bob Bradley first made his name, but no one would call the Tigers a soccer powerhouse these days. Many New Jersey-born soccer players simply choose out-of-state schools or skip the process entirely, like Tim Howard and Michael Bradley.

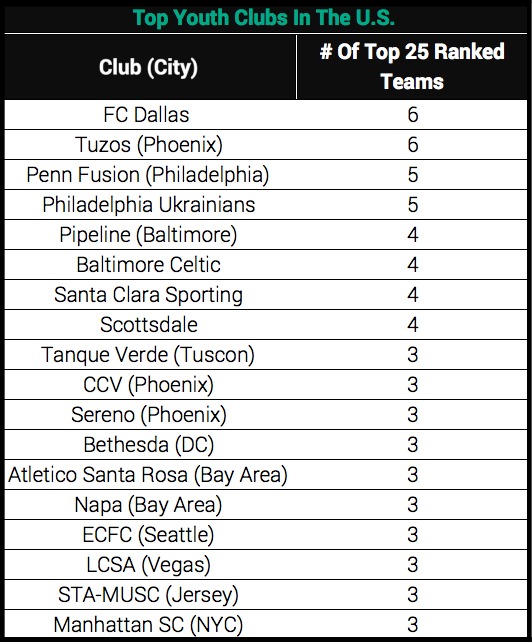

Another interesting aspect of the disparity between geography and NCAA soccer success appears when looking at the top youth clubs in the U.S. From our ranking of the top 18 youth clubs in the U.S., 10 are from regions without any collegiate soccer success of note. Five of those clubs come from Arizona, which has never produced an NCAA national champion. Two more come from the Tri-State Area and one each from Dallas, Seattle and Las Vegas.

On the flip side, a third of the clubs are from areas with direct collegiate success with three apiece from the Bay Area and D.C./Baltimore. But the fact remains: Many of the hotbeds of American soccer talent do not have successful college programs nearby.

College soccer isn’t the answer to U.S. Soccer’s woes; it’s not the reason the U.S. failed to qualify for the World Cup. But it is a factor. And while most future USMNT players would probably be better served by skipping college and going straight to the professional ranks, NCAA soccer provides additional opportunities for players to continue their careers. Late bloomers or players who slip through the cracks can help fill in gaps in the national player pool.

But men's college soccer isn’t providing that service in the areas that need it most, the areas producing the most soccer talent. A combination of well-intentioned NCAA rules, preference toward American football and general apathy toward soccer among university elites, particularly in the south, prevent college soccer from becoming an egalitarian avenue for U.S. soccer players.