And so the grand inquisition begins. Bruce Arena has stepped down as manager of the USMNT, and federation president Sunil Gulati has revealed that a short-term manager will be appointed in the “next 7-10 days” without making clear his own position with the 2018 election looming.

However, Gulati has promised a full review of the federation’s technical side, looking “at everything from our player development program, to our coaching, to our refereeing, to the pay-to-play model, to the role of education and universities, all those things.”

It’s going to be a complex process, deep diving into an extremely complex system. As MLS senior writer Matt Doyle says, “These things take time. Just tweeting isn’t going to do it.” Apart from getting involved as a coach or referee yourself to help turn this ship around, what can be done to help push the program forward?

In the days following the USMNT’s darkest hour, it’s become apparent that we have a deep desire to learn from similarly disastrous results from other nations. The most obvious case to be championed is Germany’s reversal following an abysmal Euro 2000 campaign, a 12-year, $2.7 billion top-to-bottom overhaul that later delivered the World Cup.

Don’t hold your breath.

More immediately, and at the risk of championing the quick-fix, we can turn to England’s failure to qualify for Euro 2008, the furor over the state of the Three Lions and the resulting various points of tedium that only served to detract from future success.

This isn’t meant to drag England — we’re nowhere close to having a squad with the likes of Harry Kane, Marcus Rashford, Dele Alli and John Stones — but the Special Relationship’s cultural relations can be seen in the various failures of our national sides.

Here are three pitfalls we should be keen to avoid in the national discourse or we run the risk of detracting from the discussions that actually matter.

3 Things We Shouldn't Do Following World Cup Elimination

#1. Demand An Inquisition Into And The Revealing Of A National Identity Or Philosophy

"Let's do tiki-taka now!" Photo: @Squawka | Twitter

It was easy to scoff at and become irate with Bruce Arena after he responded to a loss and subsequent World Cup elimination at the hands of Trinidad and Tobago with: “Nothing has to change.”

Obviously some things need to change. However, there is a veritable truth in what he’s saying. We’re seeing more Americans of an extremely high quality move abroad at a young age. There are now 20 free-to-play MLS academies and that number will soon be 28. It’s not terribly difficult to imagine the USMNT having achieved a qualifying record similar to that of Mexico’s in this cycle with the addition of one or two players closer to Pulisic’s quality.

Will those players, without making massive changes to the player development system, emerge in the 2022 qualifying cycle? History and common sense say absolutely. It’s mainly just a goddamn shame that this group of players couldn’t get it done this time around.

But nobody wants to hear that, especially with the pain of missing out on Russia still so raw — nobody wants to be told to be patient when that requires the passage of four more years. This will inevitably lead to calls to develop a USMNT identity — a philosophy of play like Spain or Brazil. England’s been down this road before.

“We need to clearly define ourselves tactically and technically…also socially and psychologically what our players should be like,” says Matt Crocker, Football Association head of player and coach development. “It’s like how Apple or Nike take an idea or a concept, put it into some type of process and it comes out the other end as ingrained in their culture.”

In the end, it’s hard to accept the jingoisms of philosophy, DNA and identity as anything more than pieces of intangible sophistry. As The Guardian’s Barney Ronay wrote when analyzing three of England’s most successful tournament sides (1966 World Cup, 1990 World Cup, 1996 Euros), there’s “No golden thread, no innate identity here: just opportunism and good decisions made.”

His summation of Spain’s golden generation is equally as succinct: “Spain didn’t decide to have an identity and then glue a wonderfully lucid passing game on top of this. A wonderfully gifted group of players found by trial and error a method that suited perfectly their extraordinary talents and developed these skills to a sublime degree, an entirely organic, hard-earned moment of historical ascent.”

Delving back into the USMNT’s recent history reveals much of the same. Two of the nation’s most successful international tournaments are the 2002 World Cup and the 2009 Confederations Cup.

In 2002, the U.S. went into the half up 3-1 on the world’s No. 5 ranked team, Portugal, with Pablo Mastroeni providing the defensive menace in midfield while John O’Brien utilized his technical ability to generate attacks spearheaded by the electric and fearless duo of DaMarcus Beasley and Landon Donovan.

In the Round of 16, the U.S. manhandled the world’s No. 7 ranked team, Mexico, with Mastroeni, Claudio Reyna, Eddie Lewis, Donovan and O’Brien reducing Mexico’s sumptuous midfield to futility.

In 2009, a Spanish side with a backline of Sergio Ramos, Gerard Pique, Calres Puyol and midfield of Xabi Alonso, Cesc Fabregas and Xavi could not contend with the relentless pressure and expansive athleticism generated by the likes of Donovan, Michael Bradley, Ricardo Clark, Clint Dempsey, Jozy Altidore and Charlie Davies.

The final against Brazil began in the same vein with Donovan scoring the kind of goal that would’ve made vintage Brazilian sides cry tears of joy. There is no golden thread here, and a desire to treat football like it’s an upper division college course of applied theory ultimately pales to simple opportunism and good decisions.

#2. Turn The Captaincy Into Something It’s Not

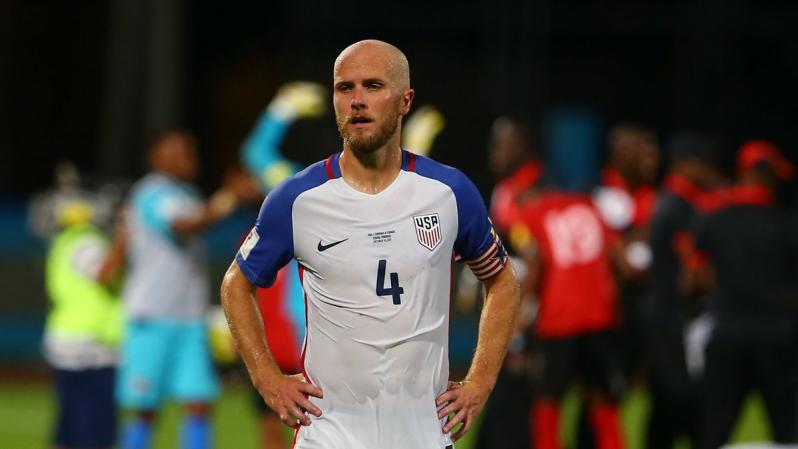

Give the armband to whoever has the most caps. Photo: @goal | Twitter

In the wake of the USMNT’s defeat to Trinidad and Tobago, calls for Michael Bradley to relinquish the armband were roundly applauded. There’s nothing inherently wrong with this charge, as the saying goes, the captain rightly goes down with his ship.

Where we risk becoming guilty of senseless rhetoric is in the call for a captain “to marshall the troops on the field” and to leave “his emotions on his sleeve.” In many ways, it’s obvious how this could be a phenomenon that appeals directly to both English and American sensibilities.

There’s nothing more American than the idea of the uber-patriot, bicep inked with eagle and American flag, bellowing the national anthem while acting as a microcosm of exceptionalism. But this doesn’t mean that Christian Pulisic should now be anointed captain for life.

Is the role actually largely ceremonial? Yes. Do countries like Italy that simply hand the armband to the player with the most caps have it right? Probably. Is Eden Hazard a terrible captain for Belgium because, as he admits, “I do not like to talk. For the national team, I am captain but I say nothing”? No.

“The English obsession with the captaincy is bizarre,” explained former England international Gary Lineker, the 1986 Ballon d’Or runner-up. “It’s purely an off the field role. Doesn’t make a blind bit of difference in games. In football all the decisions are made by the coach/manager. The captain has no say. It’s a great honor but has little influence.”

The United States should avoid turning the captaincy into a melodrama before the next cycle. Countries years ahead of us developmentally have outgrown the idea of the manager’s field marshal being represented by the armband. The sooner the appointment is met with a shrug the better.

#3. Eat Our Youth Alive

"Don't eat me alive." Photo: @usssoccer | Twitter

We are nowhere near England’s level in being able to achieve this sort of self-destructive behavior, but we’ve also reached the first moment in time when it’s actually plausible. The reason behind this is that the populace of England, its media and its whole social apparatus are infinitely more passionate about football than we are.

Great performances for club followed by terrible outings for country have long been a norm where England is concerned, but, of course, MLS isn’t the Premier League. The Gold Cup isn’t the European Championship. CONCACAF qualifiers aren’t UEFA qualifiers.

And so the hammer hasn’t fallen on any of our young players — and rightly so, particularly in the case of Pulisic. It’s too early to tell what sort of impact the elimination will have on the likes of Pulisic, DeAndre Yedlin, Paul Arriola, Kellyn Acosta, Bobby Wood, John Brooks, Jordan Morris, etc., but missing out on this tournament is hugely detrimental to their international progress.

As we don’t have near the quality of England, perhaps this point would be better defined as “Eat Our ‘Prime’ Players Alive”. It’s clear that they still have a vital role to play over the next two to three years at the least. How will supporters react to seeing the likes of Brad Guzan, Omar Gonzalez, Jorge Villafana, Darlington Nagbe, Michael Bradley and Jozy Altidore?

What will be the reception for those in MLS and for those returning to duty for the USMNT? It’s probably a good thing that November’s friendlies are scheduled to be played in Europe.

When the time eventually comes to qualify for Qatar (yeesh), any lingering hangover from Tuesday’s debacle, and it’s entirely feasible that there could still be a large one regardless of how much time has passed, will find the U.S. in an early qualifying hole again, and we all know how that plays out.

Home

Home