There was a point in Manchester City’s 21-game win streak where we ran out of things to say. To watch them is to immediately understand the profundity of Pep Guardiola’s highly drilled machinations and the osmosis of an obsession with spatial perception (here comes João Cancelo into the midfield); that and the recognition of İlkay Gündoğan as an absolute monster of the No. 8 position.

But, to borrow from Anthony Burgess, there’s always something of a “Clockwork Orange” to their achievements. The team has the appearance of a resplendent organism full of vibrant color and juice, but under the surface there’s also the clockwork toy wound by the Almighty State. There’s a mixture of the organic, life, and the mechanical, cold nothingness.

As club legend Pablo Zabaleta recently said, “When some talk about Manchester City, it’s all money, money, money. But money can’t buy you love — and I can tell you that once you play for City you feel the love.”

The money is always a punchy topic. The thread between over $700 million in spending since 2016 and City’s current pursuit of a historic quadruple leads to cynicism from both sides.

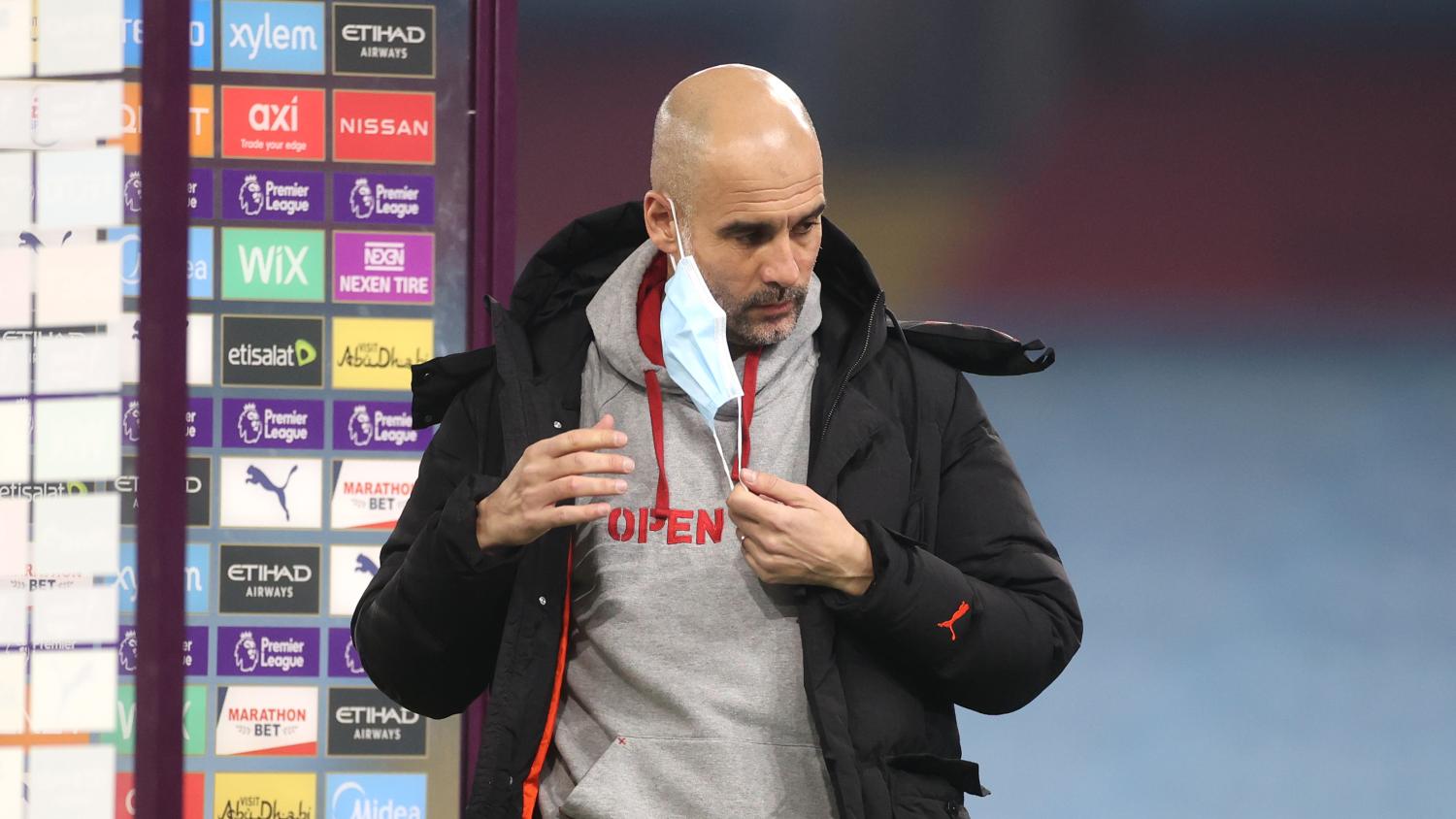

“We have a lot of money to buy a lot of incredible players,” Guardiola said when asked to explain the winning run. “It is true. Without good quality players, we cannot do it.”

This line of questioning — that City’s dominance is an unavoidable piece of determinism — understandably leaves Guardiola frustrated. It’s the belittling of a work ethic that’s legendary in coaching circles. He was, after all, labelled as “more German than the Germans” by Bayern Munich chairman Karl-Heinz Rummenigge.

And so the Spanish manager snapped again on Tuesday when effectively asked if City could beat Southampton 9-0 in Wednesday’s Premier League encounter.

“No, 18. We will score 18. 18-0 we’re going to score,” Guardiola said. “That will be the result. What a question! They (Manchester United) scored nine because it was 89 minutes 10 vs. 11 — you think it’s a joke? Come on, we’ll try to win the game.”

More than the answer (an understandable one), the line of questioning might be more revealing with regards to the mental fatigue that permeates throughout England’s top division.

There was an interesting article in The Atlantic on Monday that looked at how the pandemic is messing with our brains. One interviewee likened pandemic anxiety to a heaviness, “like you’re waking up to more of the same, and it’s never going to change.”

In a scientific sense, this can be traced to our neurochemical understanding of synaptic plasticity, which is our brain’s ability to generate new connections and learn new things. This ability strengthens or weakens over time in response to increases or decreases in activity. Our synapses have weakened over the last year as we’ve abandoned environmental enrichment and done nothing memorable. Great misfortunes can be monotonous.

As Albert Camus once said of lockdown, we come “to know the incorrigible sorrow of all prisoners and exiles, which is to live in company with a memory that serves no purpose.”

Back when the Premier League returned in June, it was heralded as “a major milestone toward normality,” but we’re now able to say that the nine months that’ve followed have been anything but normal. What do we remember of it all? Liverpool won the title sooner than any other side in history, but the celebration could only be lukewarm as celebration is defined as “engaging in enjoyable, typically social, activity.”

Aston Villa and occlusion. VAR and handballs. Marcelo Bielsa. Mason Mount. Liverpool got bad. City wins, City wins, City wins, City wins, City wins — United wins!

But the habit of despair can be worse than the feeling itself, and Guardiola and City’s response to that derby defeat is a rallying cry for moving forward in the days and months ahead: “A mix of disappointment, sadness — the second day a bit better and today completely on fire to try to do a good game tomorrow.”