The mistakes of the past are an integral part of our composition. Our future will be determined by a wide breadth of experiences and backgrounds — a collection of dissenting narratives that don’t necessarily follow the status quo. Either we allow the perspectives of the minority to illuminate the harsh truths hindering our game, or we remain insular, weakened and stagnant.

The call came while en route to an amusement park in Florida, on the line was Scott Schweitzer, head coach of the United Soccer League (USL) expansion franchise Carolina RailHawks.

Sola Abolaji was hesitant to pick up the phone. After a grueling weekend at the USL draft combine, he was looking forward to taking his mind off of soccer for a few hours.

Sitting in the car with his former club coach, Rafa, one of the only personal acquaintances to even know about Sola’s presence at the combine, he answered the call that would set in motion his professional career.

Schweitzer told Sola that the club intended to select him with the number one overall pick in the 2007 USL Draft.

“How much money do you want?” Schweitzer asked.

Now, Sola can only laugh at his response: “Uh . . . a thousand?”

Only a few months earlier, Sola had been sneaking into the school cafeteria to steal the food he needed to make it through practice. Now, the idea of getting paid to play soccer was too good to be true.

“I had an apartment!” says Sola. “I was going to practice. . .for soccer. I was getting paid. . .for soccer. I low-balled myself. I would’ve taken anything. No one was prepping me for this!”

The glamor of being the number one overall selection and earning a professional contract had never been the sole aim of his efforts.

What Sola was always prepping for, what he’d always considered the next step in his own career, was simply his transformation and evolution as a person. His dedication to the game was simply an extension of himself, the two had always been entwined.

Soccer gave Sola his true voice — the pitch allowed him to realize personal convictions that would’ve otherwise been repressed.

Photo: @ConcordeSports | Twitter

Born in Carbondale, Illinois in 1985, Sola moved back to Nigeria with his parents and brothers at the age of one. He’d spend the next four years there before returning to Illinois. His first clear memory involves the sport to which he’s devoted his life.

“I vividly remember watching the 1994 World Cup with all of my Nigerian uncles, especially the match between Nigeria and Italy. Just seeing all that excitement, the joy for everyone involved.”

His father was the student body association president at the local university in Carbondale, and they’d formed their own version of the World Cup. Playing with the sons and daughters of these students, Sola was introduced to the unifying power of the sport.

“I played with older Argentines, Saudis, Chinese and my two older brothers. They wouldn’t take it easy on me, but they’d always allow me to just jump right in.”

A tape of the Brazil vs. USA game from the 1994 World Cup became his personal bible. While other children idolized Michael Jordan, Troy Aikman and their Super Nintendo, Sola was mesmerized by the likes of Dunga, Romario and Cafu. The Abolaji family had moved into a trailer park in Illinois, but, for Sola, his mind never drifted far from the next potential game.

The Brazilian defender Dunga was Sola's idol growing up. Photo: @classic1904 | Twitter

“Every single day I’d watch that United States versus Brazil match. Then, my brothers and I would go in-between the trailers and just play. One versus one versus one, every single day. The trailers were horrible, if you hit one the whole house would just rattle like it was coming down. Our neighbors and my mother would come out and just scream at us.”

The reality of the park was that it was poverty-stricken and frequented by violence, that it had “a lake”, as young Sola thought, that was actually just raw sewage.

“I was completely oblivious to the violence of my neighborhood and the struggle of being poor. I was completely happy because I had soccer.”

Surrounded by gang violence, forced initiations and drug use, it would be tempting to call soccer an escape for Sola and his two older brothers, but soccer was merely the reality in which they lived and thrived.

“My dad would drive us two to three hours just to get my brothers to their club for practice. Two to three hours there, two to three hours back. I was unaware of it all, because, for me, it was the most awesome environment I could imagine. It was just people from all around the world that wanted to play soccer.”

One day, while playing basketball in the trailer park, an Argentine man approached him and admonished him for his choice of sport. “Africans play soccer!” exclaimed the man, running towards his trailer to retrieve a soccer ball for Sola.

Instructed to accomplish the feat of juggling the soccer ball 10 and then 100 times, he quickly became obsessed. In a trailer park of international soccer fans, Sola had his first sense of unified community.

“I considered myself a foreigner because none of the other kids at school were into soccer. If it wasn’t for them, if it wasn’t for soccer, I don’t think I would've had anything that I felt like I belonged to.”

Instead, Sola grew and developed with a larger outlook. He placed his trust and respect not to any particular nation or creed, but to the human community that shared a mutual love for the game.

When Sola was 10 years old and entering the fifth grade, his family moved to Colorado. Uprooted from the community that dictated his daily endeavors, Sola would struggle to find a fulfilling replacement throughout middle school and high school.

His father signed him up for his first foray into competitive soccer, but Sola was asked to play with an older age group. He was short and frail but the quickest player on the field.

Sola openly admits to not having the maturity level of the older kids — both his body and his mind weren’t there yet.

Alone in his age and ethnicity, Sola wasn’t looking for confirmation of his obvious talent, only for someone to speak to him as an individual and as a human being.

He was made to feel an outsider. He left practices feeling worse than the other players, not because they were better than him, but because they were white and rich.

“It’s weird saying it, but it took me all the way until my senior year of high school to get over the fact that my name wasn’t like everyone else’s on the team. I remember doing so well but only ever hearing their names. I started training to do things like the other players, like kicking it far, because I thought that’s why they always got picked.”

Sola can also recall a potluck at another player’s house where all the guys wanted to go downstairs and play video games while all the food was still out on the table.

“There was all this food. . .cherry pie, I’d never had cherry pie in my life! The other kids didn’t even eat. I remember one of the parents commenting, ‘Oh! Look at him go!’ while I was eating. I’d never been in that situation. I’d get upset when I’d see white families on TV not eating the food on the table, asking to go to their room or something.”

Privilege had previously been an abstract concept; entitlement was far from the burdens of everyday living that concerned Sola’s upbringing. Now, stumbling blocks were subtlety revealing themselves on the field and in school.

In sixth grade, he was expelled from school after allowing one of his older brother’s friends to store a gun in his locker. To this day, he still doesn’t know if the gun was real.

“In my head, I knew that he didn’t know my locker combination, so I figured it would be safe locked in there. I thought I was doing a service, that he wouldn’t be able to do anything. I wasn’t going to tell on him, he was my older brother’s friend and in the eighth grade.”

Word got out about the firearm and the police were called. They interrupted his class and questioned the 11-year-old, but Sola feigned ignorance towards the whole situation.

They opened the locker and found the gun. The expulsion process was hell on Sola’s parents. His brother’s friend eventually came clean and Sola was allowed to return for the final two months of the school year.

In eighth grade, he got perfume sprayed on him after a verbal altercation on the school bus. At school he was met with a chorus of greetings proclaiming, “You smell like a b****!”

Sola would eventually see the girl who’d sprayed the perfume on him, and he proceeded to angrily criticize her for the trouble she’d caused him.

“To her credit,” says Sola, “she just wasn’t having it. She wound back and clocked me right in the face.”

Sola ended up punching the boy standing next to her for retribution, hitting him in the chest, right above the heart. The boy staggered, fell over and split his head on the concrete, causing convulsions.

Sola was once again expelled, this time with a charge of attempted manslaughter. He landed in “The Manor”, a hellhole of an expulsion school with classmates who tested him daily.

While grounded by his parents, he consciously shifted his focus towards playing soccer. His only outlets during this dark period were old soccer videos, training alone in the backyard and sprinting inside to beat the sound of his father returning through the garage door.

“I’d throw the ball down the street because we lived on top of a hill. I’d leave the house with no soccer ball, knowing it would be just down the street. I’d grab the ball and go to an elementary field and no one would know.”

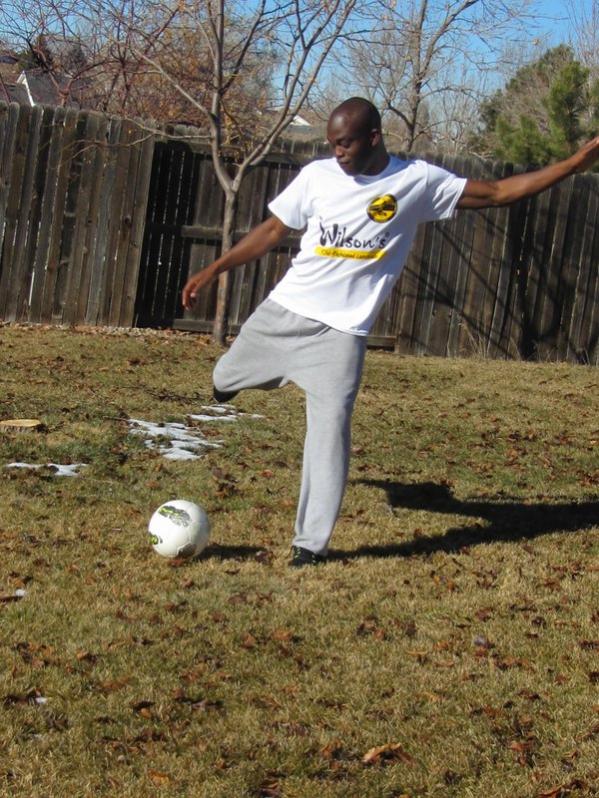

Photo: @SolaAbolaji85 | Twitter

Playing pickup soccer with his brothers remained a major source of support for Sola, but playing competitive soccer continued only sporadically.

Attending high school at Eaglecrest in Aurora, Colorado, Sola struggled to fulfill his potential with his friends joining gangs and Sola missing practices to hang out with them.

Sola’s lack of dedication eventually cost him a spot on his club team.

“I never came close to joining a gang but I was skipping out of practices, I was late to games. I gave the coach good reasons to cut me.”

Sola went from being one of the best soccer players in the state of Colorado to a player without a team. Before his junior year, his family moved out to Bennett, Colorado, population: 2,308.

The one form of punishment that had ever worked with Sola was to take away his one love: soccer. His dad had frequently taken him out of club soccer and, before his senior year, it looked like it was all over for Sola on the pitch.

Sola took all his things, his trophies, soccer paraphernalia and his very first jersey, dug a small hole in his backyard and set it all on fire.

He watched his life’s meaning go up in flames as he set about training to become a mechanic. Living in Bennett, far from everybody and everything, Sola exchanged mornings on the pitch for mornings in the machine shed.

After basically two years without competitive soccer, Sola finally convinced his dad to allow him to try out for the Eaglecrest High School team. Sola thought he was awful, the tryout hadn’t gone nearly as well as he’d hoped.

At the end of the final day of tryouts, the coach said, “Man, I thought our season was going to suck until you came.”

Eaglecrest High School Photo: @WeAreEaglecrest | Twitter

That was all the motivation Sola needed. Driving the 30 miles from Bennett to Eaglecrest everyday, Sola became solely focused on training again. Coming up against the players he’d faced off against at the highest level of club soccer, Sola held his own and then some.

With Sola at the heart of their defense, Eaglecrest hardly lost. He grew by leaps and bounds throughout his senior year while another coach offered to videotape games and send them to colleges for recruiting.

However, expelled and suspended for as long as Sola was, he was way behind his classmates academically. Both science and math were difficult subjects for him, and a trip to Las Vegas with an adult team elicited interest from UNLV that was quickly quelled by his grades.

While players he’d known since the fifth and sixth grades were getting full rides to colleges like Denver and Stanford, Sola eventually landed in Great Bend, Kansas, at Barton Community College.

In a city built largely on agriculture and a declining oil industry, where 13.7 percent of the population lives below the poverty line, Barton CC’s motto, “What drives you?”, could be read as a call for prioritizing an exit strategy.

Downtown Great Bend, Kansas Photo: Wikipedia

On the first day of practice, in an act of “good will” from the coach, Sola and his teammates were advised against leaving campus alone.

“Our coach sat all the black kids down, and we had a lot of black players, and literally told us, ‘Stay in your group. Don’t leave campus without one another. If you need anything off campus, call me and let me know. I’ll go and get it for you.’”

Racism, fighting and drug abuse surrounded Sola at Barton, and then the third expulsion of his academic life took place.

“I was talking in class, I was being disruptive,” says Sola. “The teacher told me to be quiet. Fair enough. Then, this guy in class goes, ‘You can’t tell him to be quiet, he’s a superstar!’”.

Sola had just been in the local newspaper. In small towns, the local newspaper is everything. In Barton’s newspaper, the front page was reserved for special achievements or human interest stories, and the back page was reserved for police blotter, criminal activity and the like.

“Yeah?” the teacher reportedly said. “Probably on the back page.”

Sola was indignant, calling out the teacher’s own credentials at a community college in Barton. After being told to stay after class for further admonishment, Sola went to practice. He told his coach that he’d been involved in an argument with his teacher, but he hoped that would be the end of it.

The teacher reported to university officials that she’d been threatened. Going into regionals with a squad that was poised to win the NJCAA Region VI championship, Sola was barred from participating during the investigation.

“I’d been expelled from every stage,” recalls a visibly distraught Sola, “and I was about to get expelled from college. I couldn’t believe it.”

Sola neglected to tell his parents, worried this latest expulsion process would be too much for them to bear.

Photo: @bigsoccer | Twitter

At the rehearing, his expulsion was confirmed. However, the assistant president of the university helped him into Northern Oklahoma community college with a letter of recommendation.

“What you did was wrong,” Sola remembers the woman saying, “but you’re not being expelled for what you did. You’re being expelled because you’re black.”

At Northern Oklahoma, Sola found himself in another less-than-accommodating environment. But, reminiscent of his childhood in Illinois, he found himself surrounded by a community of individuals devoted to the game.

He trained day in and day out, playing through the pain of an injured ankle to try to attract the interest of top universities around the country. After a successful sophomore season, he decided to sign with the University of Buffalo.

Sola was eager to make a name for himself, to inject a program with a level of skill and dedication that would shake-up the existing culture.

The team wasn’t any good, but Sola’s new dream was to take “a shitty team to the NCAA finals”. If they met his brother’s Stanford side on the way, all the better.

Buffalo coach John Astudillo ensured Sola maintained the grades and the mentality necessary to remain a key player on the squad, making Sola promise to see out what he’d started on his own accord.

At times, Sola would be without money and without support. He’d walk into conferences on campus, grab a random name tag off of the sign-in table and begin to mingle with guests just to eat their food. If he wanted to practice everyday, he needed to find a way to fuel himself.

“I’d wake up early, train, catch the school bus into campus and try to find something for breakfast, lunch and dinner. That was the grind. Players from other countries, people like Luis Suarez, Antonio Valencia and Carlos Tevez, that was my kind of solidarity - I was sacrificing for soccer. Mommy and daddy weren’t taking care of me, I was doing this for soccer.”

At the time, professional soccer in the US was nascent and dealing with its own growing pains. The idea of being a professional soccer player hadn’t entered Sola’s mind.

“All I wanted to do was play for Nigeria, the United States or Duke University. I had no idea that you could get payed to play, I was sold to the game. I thought I’d relate to people at college, I thought everyone would be there for soccer. But people were there for girls, school or just to look cool. I’d be training at 2 AM — it’s like living on an island. No one understands you outside of a couple people.”

Primarily used off the bench to counter whatever the opposition team’s strongest point was, Sola went largely under the radar until the USL draft. His own development sacrificed for the sake of winning in college, Sola carried two years of hurt into his showing at the combine.

He had spent the last month training religiously in New Jersey. The event had promised to be free of the favoritism and partiality which had seemingly plagued his time in Buffalo.

At the combine, every player had a profile detailing their accolades, awards, accomplishments and various biographical information. Sola’s player card had his name, school and phone number.

Liberated by the realization that personal skill and resolve would be the sole rulers of his career moving forward, he played some of the best soccer of his life — flourishing under the watchful eyes of professional coaches and scouts.

Selected by an expansion franchise with the first pick of the draft, Sola embarked on his professional career with only a noxious agent by his side.

He had no idea as to how to care for his body at the professional level, and he suffered from jumper’s knee and a torn MCL before he could make his professional debut. After only 10 games with Carolina, he was traded to the Vancouver Whitecaps.

In Vancouver, a goalkeeper by the name of Lutz Pfannenstiel, remembered in the world of soccer as the only player to have played professionally in all six FIFA confederations, told Sola he needed to get out of the United States professional system.

Lutz Pfannenstiel played in all six FIFA confederations. Photo: @delinquentweet | Twitter

Sola says his agent had been telling him fabricated stories about deals that were certain in the US while pushing him to go on trial with clubs abroad. Disillusioned with the emphasis on size and physical attributes in US development, Sola purchased a ticket to Europe.

He’d been advised against continuing to employ his agent after his trade to Vancouver, but Sola trusted his advice regarding earning a potential contract in Western or Central Europe.

After a turbulent debut season in the USL, the change of scenery couldn’t come soon enough.

Days before his expected departure, his agent mysteriously disappeared, never to be heard from again. Having already purchased the ticket, Sola got on the plane and tried to make it in Europe by knocking on doors and attempting to seamlessly sneak onto the training field in full kit.

Getting a chance to even demonstrate his abilities proved difficult.

A sympathetic player on Rapid Vienna, a club in Austria, went as far as claiming Sola as “a friend” so he could train with them. This led to a meeting with the sports director wherein Sola, fearful of not getting a chance to at least demonstrate his abilities, claimed he was a Nigerian youth international.

Sporting directors of top European clubs are weary of walk-ons, especially so of American walk-ons. After consulting his database of recent Nigerian youth internationals, Sola’s fib was discovered, and he was asked to leave the premises.

Sleeping in train stations, pocketing extra bread from restaurants and working out with clubs in Austria and Germany, Sola was troubled by the monetary aspect of smaller clubs only interested in signing him for a larger selling-on fee, or by clubs unreceptive to his presence.

In Bonn, a city in Germany on the banks of the Rhine, players refused to shake his hand because he was seen as someone coming to take another player’s place in the squad. Throughout it all, only the African players seemed to recognize what he was going through.

“If you’re African, and you come to a team, you make the other African guys feel more comfortable. You each recognize the struggle, because African players get treated like shit.”

A sports hernia ended any plans of joining a team in Europe, and a rescinded contract with the Minnesota Stars back in the states left Sola in the lurch.

Over the course of a couple years, his professional career had sent him across both North America and Europe, leaving him without a club, without money and skeptical of empty promises.

Sola ended up signing for the Thunder Bay Chill in Thunder Bay, Ontario, in the PDL, the fourth tier of the American Soccer Pyramid. While Ontario isn’t exactly synonymous with elite soccer, the professional, family oriented style of the club directly appealed to Sola.

Photo: @ThunderBayChill | Twitter

After the continuous pressures of having to prove himself over and over again in Europe, Thunder Bay provided the perfect respite. “Look, you don’t have to perform at your best right now,” Sola’s coach at Thunder Bay told him. “Just relax, get some touches and we’ll get you in.”

Appearing in 25 matches for Thunder Bay, Sola became influential on the field. Off the field, the club’s nutrition expert was the first person in his four years as a professional to teach him the importance of proteins, recovery and taking care of his body.

Once again healthy and advised by a friend to tryout in Sweden with Enkopings SK, Sola gave Europe another try. He was signed by the team but faced adversity in the forms of uncertainty and financial difficulties.

“It was just a shit show. You weren’t getting paid,” says Sola. “I had no money, zero. They gave me a nice little apartment, but I didn’t tell anybody that I had no money. I thought I’d be getting paid. There were days I didn’t have any food.”

He met two Ethiopians living near his flat who were “literally life savers”. They’d invite him over for lunch and dinner. They’d take him out and pay for everything.

“I didn’t like people taking care of me. But this guy would keep knocking on my apartment door: ‘I know you’re in there! Come on, hunny!’ He’d just force me to come out with him and I’d eat. I’d have food.”

Although Sola had the energy and commitment to train again, he still hadn’t been paid, and the situation facing him forced him to look for a new club.

A positive tryout in Norway had Sola feeling confident about the next step in his professional career. He’d played well in front of officials from Stabaek, a club that had another American on their roster in Mix Diskerud.

Sola settled into a rhythm, essentially working around the clock on his game. He’d found an interconnected community were soccer was at the center of his well-being.

Photo: @ConcordeSports | Twitter

Then, in a moment, it was lost when he suffered a broken knee cap in training. Knowing that this might be his last chance abroad, he kept running and trying to push himself, but the damage had been done.

Club officials told him that, when healthy, he should return immediately. However, Sola had no money and no health insurance. There was no way he would be able to afford the medical costs, it was over.

That’s when Bret Hall, the former assistant of the U.S. Women’s national team, entered the picture. A coach who’d worked directly with Michael Bradley, Jonathan Spector, Abby Wambach and Hope Solo, Hall told Sola that he “could be the next Jay DeMerit”, an unsung defender from Green Bay, Wisconsin, who won 25 caps with the US national team.

The costs of his surgery, recovery and rehabilitation were completely covered.

“They didn’t ask for a single dollar. I don’t know how they convinced the doctors or the hospital to do it, but they didn’t ask for a single dollar.”

With his leg in a brace for two months, unable to bend it or play soccer at all, Sola began focusing on coaching for the first time. Unable to show his players what to do, he concentrated on describing things with the minutest of details.

After recovering, another stint in Norway fueled Sola’s coaching desire. He trained with the women’s team when he wasn’t playing, he spent all of his time off the pitch watching training sessions and talking about the game with people who lived and breathed the sport.

Photo: @SolaAbolaji85 | Twitter

His hunger for a collective mindset was satisfied. He found clubs working for the betterment of individuals with the long-term goal of creating a unified collective. This attitude struck a chord with Sola.

Sola believes that his insights into a multitude of communities across Europe sheds an invaluable light on what’s important with regards to player development.

“The communities love their club. The things we did during training just weren’t being done anywhere in the United States outside of MLS. You would’ve thought we were Barcelona or Arsenal, but it was all about developing players in a certain way. Here in the United States, everyone is a genius, everyone knows what to do. They’ll say things that are beneficial for themselves. Out there, it’s all about the team. If it doesn’t benefit the team, there’s an issue.”

Photo: @ConcordeSports | Twitter

Sola realized that each European club has it’s own specific brand, it’s own way of playing. The smaller clubs know they don’t have the resources to attract elite athletes, so they must be hyper-conscious of player development.

For Sola, the US youth soccer system is too padded. Everyone’s made to feel too comfortable with adversity and failure made nonexistent. Privilege, familiarity and contentment breeds an environment of complacency, one in which players are never made to go above and beyond a lower performance baseline.

“You need to feel failure and to have challenges,” says Sola. “We’re not looking at the future or the kid’s development. Instead of looking at who the kid can become, we look at who he is now. There has to be a level of discomfort. There has to be a level of real challenge.”

Sola believes it’s all about delivering this challenge in an environment that supports the individual needs of its players. Sola is now 31 years old. His main priority has shifted towards taking Nisola Futbol Academy, his individualized soccer training program, to the next level.

Photo: @SolaAbolaji85 | Twitter

He’s not concerned with sending the most players to Division I soccer programs or telling kids that they’ll someday represent the national team, but he is concerned with using soccer as a tool for daily growth.

“I’m trying to make it an even playing field. Show up, you’ll get the same kind of treatment, the same kind of training as everybody else. One of the biggest mistakes is that coaches focus solely on the talent and not on the human being.”

Throughout Sola’s life he’s been able to rely on like-minded individuals who prioritized being genuine above all else. He found these individuals frequently through soccer, a common denominator that abolishes differences of race, gender and class.

A saying from the Book of Proverbs encapsulates his idea for a successful soccer academy: “As iron sharpens iron, so one person sharpens another.”

Reared by the adverse situations in his life and forged by communities, both at home and abroad, that value desire and passion above all else, Sola Abolaji stands as a testament towards a necessary shift in the American soccer dialogue.

Follow me on Twitter: @ConmanFleming