Chances are, if you’ve done soccer, you’ll know about goals. But what are they? How does a goal become a goal and not something else? When will you know if you’ve actually seen a goal?

These are all good, valid questions. You see, all goals are created equal, but not really. Goals come in all shapes and sizes, and you never really see the same goal twice.

At the most basic level, a goal is a goal when the ball crosses the goal line in its entirety. That’s really what a goal is. That’s really the science behind it in a nutshell, I guess.

But how would you explain a goal to someone with an impairment that stopped them from seeing nets and lines and posts and stopped them from understanding the concepts of those things?

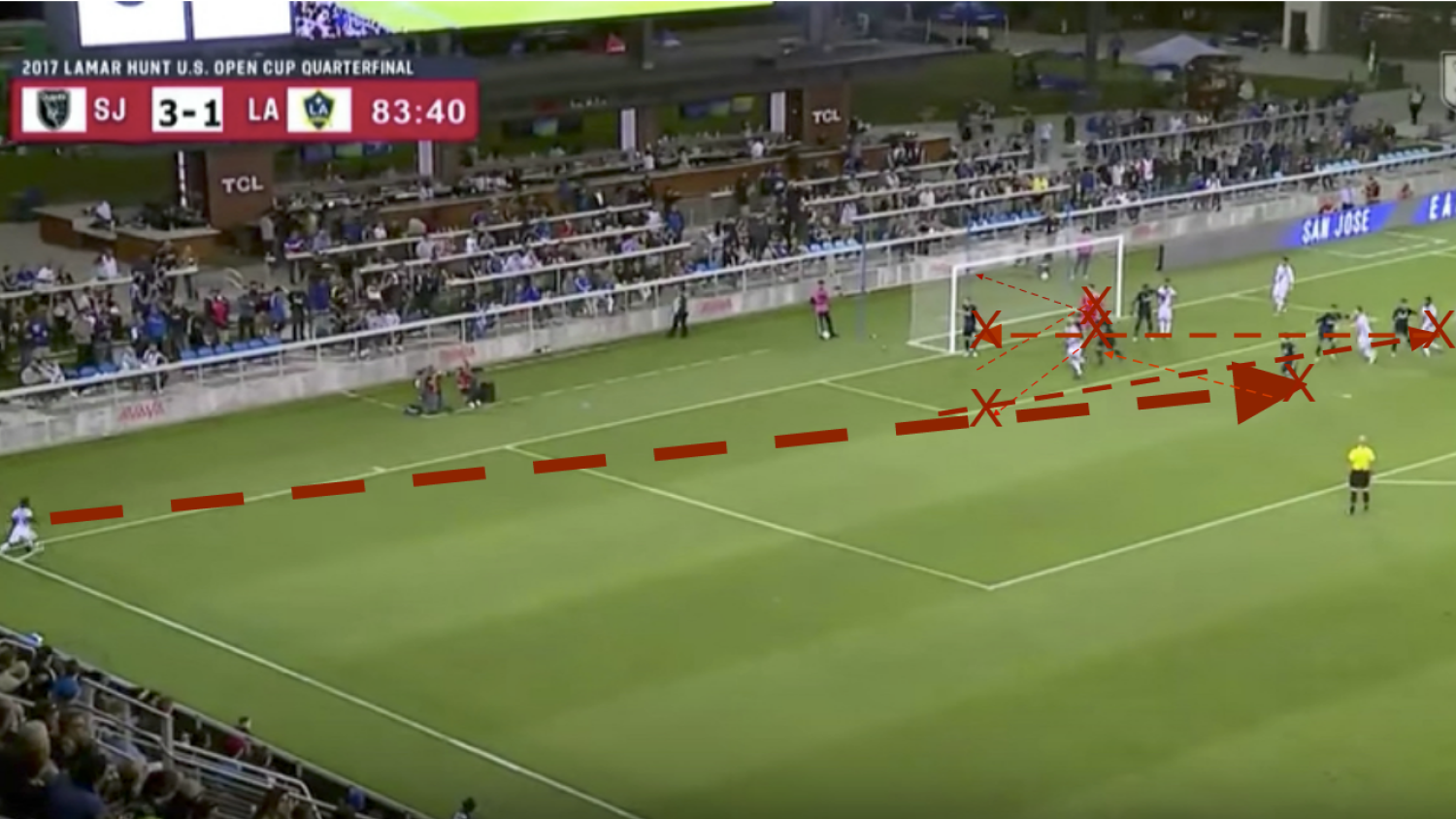

Let’s look at a goal as a concrete example of what a goal is. Here we have the San Jose Earthquakes taking on the Los Angeles Galaxy in the U.S. Open Cup quarterfinals.

This series of events begins with a corner kick, which might look like a goal with the ball so close to the end line, but it’s not yet a goal. The corner is an out swinger, and it’s dashingly met with a brave header planted on net. It goes near the goal, but it’s not yet a goal. There’s a defender who kicks it to the edge of the six-yard box. Then another defender kicks it. Still no goal up in here.

It runs across the box and meets another attacker. He strikes towards net and it reaches another defender, but a quick look at our goal-line technology reveals, nope, still no goal.

The defender hits it to the goalkeeper but not yet a goal. It hits the keeper and goes into the net. Goal. That’s the part that’s a goal, and now you know how goals are made, and it has nothing to do with two naked people rolling around.